Image by KoLa Entertaiments from Pixabay

It was too cold to be walking barefoot in the creek, but children tend not to concern themselves with the weather like old folks. They also maintain some nescience to the pain and mortality of this world and so let their feet numb in the water without wasting another thought on it. The sky was gray with the promise of rain, and the wind blew in from the southwest. Not that it mattered to them. It was daytime and that meant something needed to be done. Something always needed doing during the day. They wouldn’t be caught dead inside unless they were sleeping. They needed to be out doing, working hard at getting absolutely nothing done, and this day was no different from any other.

“Grab my hand, Gid,” the taller boy with the dark hair reached behind him.

“I got it myself,” the younger boy replied, his sandy hair almost to his eyes looked like a bird had nested in it. He slapped at the other’s hand but missed.

“Ahight, but you fall in this water, and I ain’t taking you back to the house cause you’re cold.”

The younger boy shrugged his shoulders and stepped knee-deep into the water with his very next step. He cussed under his breath and kept walking. The boy behind him giggled but didn’t say anything. They walked on in silence for a time, and the open pasture began to give way to trees and more trees until they were in the woods entirely. Never did they leave the creek bed, which at times had eroded six feet into the earth, at other times eight. When their idea of a chasm presented itself, they went to work trying to climb out and sliding down, each determined to show he had the better agility. They would dig their filthy fingers and toes under tree roots to create holds in the red clay banks then they would ease through the once clear water they’d made muddy looking for whatever presented itself, an arrowhead or piece of Cherokee pottery the ultimate prize. After losing patience with his search, the smallest of the group shoved his hands in his pockets and kicked the water.

“This ain’t worth nothin, Airn. This is bout the same thing we always do. It’s either this or fly June bugs or hit the dog or build a fort, and I’m tired of doing that stuff. The good weather’s gone and school’s back in. I’m gohn go crazy if I don’t do something else, I tell ya.” He looked up at the other boys as tough as he could and waited for a reply. After a few breaths, they went back to scaling their mud wall and looking through the water.

“To hell with y’all,” Gid said and kicked the water right where Aaron was looking for treasure and started walking downstream. Aaron caught him with a slap on the back of his head, but the little one only stumbled and kept walking.

“And just where in blue blazes do you think you’re going? That fence right there is the end of our land.”

Gid didn’t respond. He looked up at the five strands of barbed wire, the bottom strand being at the level of his head, then he looked at the two posts buried sideways in the earth across the creek. He stood in front of the posts, the two boys watching him from up the water, then planted his head and shoulders between the pieces of wood and crawled through. He could hear the splashes of the other boys running as he planted both feet on the other side.

“Dammit, Gid what are you doin? Daddy said we could do whatever the hell we wanted so long as we didn’t leave the property,” he was looking through the posts while his little brother stood with his back to him on the other side. “I ain’t had a whoopin in a long time, at least a month, and I don’t want one today because of your sorry little ass.”

“Watch my sorry little ass,” he replied, swishing it back and forth a few times with his first steps away from the fence.

“He gohn get y’all tow up fuh sho, Airn,” the boy said from behind him.

“Come on, Zeke,” Aaron replied and started climbing through the posts. He had the hardest time with it. The posts were just too close together, and he rubbed his chest raw through his shirt as he went through. Zeke was a little smaller, but it wouldn’t have mattered. He glided through the wood easier than little Gid and came out on the other side smiling.

If they had thought to intimidate the boy, they failed. Gid never broke stride even as the thumping of their feet approached him. Aaron followed a few steps, expecting the boy to run, then finally just grabbed him by the shoulders when he wouldn’t stop. Gid snatched away and turned around furiously with his hands out by his sides looking to fight. Aaron went to grab him again and haul his younger brother to the ground in order to give him a good beating like he’d done so many times, but he stopped before taking a single step. He knew nothing would come of it anyway except to make Gid all the madder. Last time, he’d waited over an hour until Aaron wasn’t looking and near knocked his lights out with a garden rock the size of his fist.

“Look, I’m all for it,” Aaron threw his hands up in surrender then shoved them in his pockets before he continued. “I see what you’re saying, and I’ve got no problem with it. We’ll follow this creek down to where it ends on the other side of Jasper Church if you want, but not right now, not today.” He pointed up to the sky to make his point.

“It’s about to rain, Gid. Hell, you can smell it, and it ain’t gonna be a nice cool summer rain. It’ll give us all our death of pneumonia.” Zeke shook his head and smiled while the larger Aaron pleaded with the much smaller Gideon. These folks were a trip. “Come on, buddy. Let’s just go back to the mud walls and mess around as long as we can. Maybe Zeke can even get up there and get the rope down from the tree limb so we can swing. Come on, we’ll go with ya some other time, I promise. We’ll go tomorrow, Lord willin and the creek don’t rise.”

Gid lowered his hands and relaxed his shoulders. He turned his head and looked down the branch as far as he could then he looked back at his brother. His feet were pink with cold, and all he had on other than his rolled-up jeans was a faded green tee shirt with a torn pocket.

“Awright, but I’m coming down here again to see how far this goes with or without y’all, and you can etch it in stone.”

Aaron chuckled a little at his little brother stealing one of Mama’s expressions. He looked just like her, his short little mean ass. “All right, it’s a deal,” and they made their way back up to the posts to squeeze their way through.

___

The smell of moth balls and peppermint lingered in the stagnant air. Sporadic coughing and the creaking wood of pews were all that broke the monotone voice of the preacher as he talked about what needed to be done but mostly what must be avoided in order to live a good life and make it to some place better. Mama would look over at them if they started to get too loud and give them the look. She pulled a program from her purse and handed it to Aaron. He grabbed a hymnal from the back of the pew in front of him on which to press down then grabbed the stubby half pencil in the slot beside the offering envelopes and began shading in the outline of the church on the cover. Gid looked around and had to slide down to the end of the pew to get another pencil. He leaned shoulder to shoulder with his brother and began helping in the artwork. It worked out well since he was left-handed while his brother was right.

On the other side of Mama sat their little sister in her poofy dress. She was always on the other side and out of the way. She mixed with them about like wax and water. A little repellent if there ever was one. Mama kept her comfortable in candy and coloring books on the other side where she’d stay defused while the preacher droned on.

“Your bodies are but vessels for your souls as It says in Thessalonians, brothers and sisters. There are too many who would seek what is right in this world for the nourishment of sin rather than live in austerity for this brief moment in order to sit in the kingdom for eternity. Liquor, lust, money, these are the fuels which the fires of hell burn on, and the joy you may think they bring you in this brief passing, this heartbeat of time, will only bring you down to the depths of his kingdom, the kingdom of Satan that is happy to indulge you as you have indulged—”

“What’s austerity?” Gid whispered to his brother without lifting his head from his pencil strokes.

“I don’t know,” Aaron stopped shading for a moment and looked forward then he went back to work. “I guess it’s what you get for doing bad things.” He scooted over a little when he got a nudge from his mother. He looked up at her with mouth open then looked over at Gid and shook his head.

Aaron sniffed loudly and wiped at his nose with the back of his hand. He looked up to see old lady Watkins looking over her shoulder at him from the next pew. Smiling her awkward smile with false teeth too large for her mouth, she leaned back and handed him a peppermint. Aaron reached for it happily then stayed his hand and looked over at Mama who gave him a small nod in permission. Gid looked over at him as he opened the plastic wrapper as noiselessly as he could then he looked up and made a face of disgust at the old lady. She turned around when she spied his reaction to his brother’s candy.

“That’s the only one I had,” she whispered then turned the back of her head to him. Gid shoved the pencil back in the slot and slid down the pew. Aaron placed the candy in the side of his mouth and crunched down on it. The noise was so loud the preacher actually looked in his direction. Aaron paused for a moment, looking down and waiting for the resumption of the sermon, the return of the atmosphere, and the aversion of his mother’s gaze that he could feel on the back of his neck. Smiling a little, he looked over at his brother and held out the jagged piece of candy that stuck between his fingers. Gid grinned and took it quickly.

“Look at the rewards that await you all from a merciful God. You will be in His presence, bathed in His glory in heaven. All those you knew and loved, those who have gone before and will after, so long as they walk the path will be there for you. You will get to spend eternity with them. All others will be left behind to face the final judgment or be swept away to a place absent of God, a place away from His presence. First Corinthians tells us that heaven is a place of infinite peace. Man cannot even imagine—“

“What if you don’t like the people you’ve been around while you’re alive?” Gid began shading between the letters on the program after the picture of the church was done. “I mean, how much would you look forward to bein around Aunt Bertha in heaven? I mean, if she gets in and all. Is that supposed to be peaceful?”

“I think everybody has to act right up there, you know,” Aaron brushed his hand to the side then turned the program over so they could shade the cross. “I mean, you don’t act the same way you did when you were alive. They’re quiet or maybe you don’t have to listen to them up there.”

“If you don’t act the same way you did when you was alive then how did you get to heaven in the first place?”

Aaron sighed and shook his head as they continued their work, “I don’t know. I guess you’re not supposed to understand how it is, like the man says.

On the way out, the preacher squeezed his hand too hard and mussed his hair like he always did. He just grinned at the mean looking old man as he’d trained himself to do, but he heard Gid grunt and pull away as he did it to him. They walked behind Mama and little sister to the car, Gid trying to sneak past Aaron into the front seat only to get shoved back like always.

“Gideon, now sit down while we’re in town,” Mama said, looking at him in the mirror. “I don’t want to have to pull this car over again.”

Daddy was in the yard throwing chicken feed when they pulled in. The boys ran inside, shedding their ankle-high slacks, clip-on ties, and the rest of their Sunday gear as they went. Mama went to the kitchen and immediately started dinner, and the boys shuffled in with her after a few minutes with their outside clothes on, hands in pockets waiting for her to acknowledge them. Gid began to shuffle his feet with impatience.

“What is it?” she asked while spreading mayonnaise over the bread next to what was left of the ham.

“Can we go?”

“After you eat.

“Can we eat while we go?” Aaron looked back at Gid, but he just kept his head down for fear of Mama saying no just despite him.

“Go on and take your sandwiches. You can drink out of the hose I reckon. I don’t want you leaving my glasses outside.

They grabbed the ham sandwiches and headed out, the screen door slamming behind them. They almost hit Daddy coming up the porch steps.

“Where y’all goin?” he asked without stopping.

“Down to the bottom.” The door shut on Aaron’s last word. Daddy never even stopped walking. The two boys just glanced at each other and shrugged. They ate their sandwiches in no more than four bites and sucked down some water from the hose on the side of the barn.

“We goin to get Zeke first? You know colored folks stay in church a heap longer than we do.” Gid spoke while he eased between the barbed wire strands of the first fence.

“He’s likely already down there waitin on us,” Aaron replied. “He said he was gonna sneak outta church the first chance he got. Said he could do it right after he helped pick up one of the folks in back when they fainted.”

“What do they faint from? It ain’t hot no more.”

“I reckon it’s the spirit they feel or somethin. That’s what I heard.”

“If you say so,” the younger replied, and they picked up their pace in the open field in order to save time.

___

Ezekiel waited for them at the creek. He was trying to skip rocks down the middle of the water, but the creek was too narrow to yield any success. He turned and followed them when they walked past, his Sunday pants still on, rolled up to the knee despite the weather. He had to leave his good shoes at their starting point. They’d have to be there when they got back because he wasn’t about to risk messing up his good shoes. If his mama didn’t skin him for it, his grandma would. The black wingtips that were stuffed with newspaper at the toes had belonged to his granddaddy.

They walked along the side of the creek this time, having sore feet from the cold the day before, and they listened only to the sound of the wind and each other’s footsteps. Whatever was to be said was left in their mouths until someone dared break the silence. They walked with heads down, Gid in the lead swinging a stick back and forth in front of him like a blind man checking his path. As they approached the edge of the woods, Zeke stopped and looked back up the field.

“Look yonder,” he said when the two boys didn’t stop with him. Aaron and Gid both turned to him then followed his eyes up the hill.

“Oh hell naw,” Gid squeaked out. “ What in the bumblin name of Beauregard is this shit here?”

Aaron snorted a laugh, and Zeke shook his head. There was just never any telling what was going to come out of Gideon’s mouth at any time, but what he said was certainly warranted here.

Running down the hill far too fast for her legs to carry her was their little sister. She wore a pink and white dress with ruffles not quite to the knee, white stockings, and patent leather black dress shoes with gold buckles. The outfit was topped off with a matching pink bow in her hair. She carried something in her hands that looked like clothes, maybe pants or something. Nearly face planting twice, she approached them huffing and puffing like a fat man putting on his shoes.

“What the hell are you doing, Dookie?” Aaron stepped forward before Gid could harass her.

“I’m—puh,” she bent over and huffed a few more times before she could continue. “I’m goin with y’all.”

“The hell you say!” Gid said, and Aaron held a hand up to him. Zeke just watched, continuously shaking his head. These folks were a trip.

“You can’t go with us, Dookie,” Aaron said calmly. “We’re going in the woods, and you ain’t hardly dressed for it. The briars would tear them stocking and your legs to pieces.”

“That’s why I brung these,” she held up the pants and shirt she had in her hands. “Mama said I can wear em.”

“Those are my damn clothes!” Gid said, and Aaron shushed him again.

“Mama knows you’re down here?”

“Yeah, Daddy does too. He says y’all got to take me. I want to hunt crawfish too.”

“We ain’t huntin crawfish,” Gid said.

“They ain’t no other reason to come down here,” she had her hands on her hips and her head cocked to the side like she was explaining something to an imbecile.

“Yes, there is,” Gid hissed.

“What?”

“We ain’t tellin you, you little snitch. Don’t matter no way. Daddy’s little angel can’t go in the woods. She might bite a snake. Or maybe it’s the other way around. Go on back to the house, Dookie.”

The name was one of affection that had evolved or rather devolved from the Lookie that came from Lump. Her given name was Loretta, but no one called her that, not even their grandmother, after whom she was named. She usually called her Lump, but her brothers never called her anything but Dookie.

She looked hard at Gideon who was two years older but no bigger than she was. Her little face was scrunched up like she’d just sucked a lemon. Mad as hell. Aaron stepped in front of him, and Zeke stepped off to the side so he could still see. Dookie eyed him.

“I’m goin with y’all or I’ll tell Mammy Zeke wore his Sunday pants out here. I reckon his shoes are around here somewhere.”

“Whoa whoa now, Dookie,” Zeke threw his arms up. “Why you gohn do dat to me? I ain’t got nothin to do with dis.”

“Yeah, now Dook,” Aaron chimed in, “that ain’t called for. All you’d do is get Zeke whooped, and he don’t deserve that.”

“Well, take me with y’all then, and you ain’t got to worry bout it.”

“You ain’t goin with us, Dookie—eater.” Gideon yelled over Aaron’s shoulder.

“You shut up! Don’t nobody listen to you no way, half pint. You little pip squeak,” the girl replied, and Aaron had to catch Gid midflight from jumping on their sister. The girl just laughed then shrugged her shoulders like the matter had been settled. “What are we even talkin about? I’m goin right with you. What you gohn do, carry me back to the house?”

Aaron shook Gid hard and set him down, then he looked at Zeke who continued shaking his head.

“Hot damn, we ain’t got time for this,” the oldest said and started walking. “Let’s just go. You better hurry up and put them clothes on, Dookie, if you want to keep up.”

Zeke and Gid watched the girl pull the pants over her stockings then put the shirt on. It was cool out, no more than upper forties, but not a one of them cared. The sun was up, they weren’t in school, and they weren’t in church. There were things to be done not to be overseen, and they weren’t about to let their spoiled little sister take that from them.

They followed the creek with Gid leading the way like he weighed two-hundred pounds. He could’ve stepped on a moccasin or straight through poison oak. It didn’t matter to him because he was still at the age of invincibility. Aaron followed him, mostly to see he wasn’t hurt, while Dookie and Zeke brought up the rear. The wind was cutting through the trees, and had they been adults they’d have been uncomfortable, but as it was, the mysteries and wonders of the world still revealed themselves to their eyes not yet dulled by time and experience.

___

The quartet worked its way through the briars and the brambles, the thorns and the thistles. She liked the sound of nature’s needles scraping across the fabric of Gid’s jeans that fit rather well over her stockings. Her good shoes were getting scuffed, but Mama would fix them. She always did. Short of Dookie taking a knife blade to them, there’s nothing she could do that Mama couldn’t fix.

The woods were a mix of brown and gray, a colorless cold. Their footsteps were sporadic, long, and dragging. Squirrels scurried up trunks at their approach or jumped from one tree to another. Crows cawed in the distance, always in the distance. They crossed three fences, and Dookie was both scared and excited at the same time. She’d never been so far from the house on foot. Her dress rubbed her underneath the shirt, and she knew she looked silly as a goose with her ruffles sticking out of the shirt and the bulges of the material showing all over.

“You ever been this far before, Airn?” Dookie asked her older brother for about the tenth time.

“I told you I have. I’ve been all the way to Jasper Church Road.”

“You ain’t neither,” she gave her usual reply, and Aaron said nothing else to her about it.

The minutes turned into an hour that began to close in on another when Gid hit his walking stick against a hickory that was too much for it. The break was loud, and he threw the remainder at the tree as if he could hurt it, then he stopped and stared through the gray trunks and underbrush.

“What is it?” Aaron asked.

“How far are we from the road?” Gid asked and pulled up the bottom of his shirt to wipe his red nose.

“A long way, I reckon. We can’t be no more than halfway between our property and the road.”

Gid made his way down the embankment and crossed the creek without looking back at them. Dookie and the rest tried to see what he was looking at.

“Then how the hell is that out here?” Gid asked, and the others slid down the dirt and followed.

It was a house of sorts—well it had been at one time—but it had burned on the inside because it was black around the windows and the door. It was white and set on stacked stones that held it up at the corners about three feet off the ground. Much larger than their own house, it was almost as big as their barn. The porch was still intact, and red brick steps were set in front of its center. There was a well house on the side and a bird bath with the top on its side next to the concrete stand, but there was nothing else. There wasn’t even the suggestion of a driveway. Gid walked right up to the steps.

“Whoa, hold on now,” Aaron said, stepping quickly behind him. “You can’t just go up in somebody’s house.”

“Don’t nobody live here,” his little brother replied. “It burn up at some point. I just want to see how it looks inside.”

“You can’t,” said Dookie. “What if it falls in on you.”

“Yeah, it’s been standin here all this time. Holdin on just so it could fall on the first poor bastard to walk in.”

“Go on then,” little sister replied. “If it knew you well enough, that’s exactly what it’d do.”

He only got to the third step before they all fell in line behind him.

The porch was sturdy beneath their feet. It was that kind of wood on nice houses, rich folks’ houses. It was hard and unbending under the feet. None of the boards of the porch showed signs of burning, but when they got to the door Gid ran a finger down the soot at the edge of the frame and pulled it away for them to see the black powder on his pink digit.

“Don’t get your dress dirty,” he grinned at his little sister.

“Shut up,” she replied, pulling on her shirt so he looked at it. “Everything I got on is yours. Don’t worry bout me, half pint.”

Inside was dim since only the sunlight that made it through the trees and the dirty windows lit the house. Most of the windows they could see were still intact. The walls and floor were black in places, but the ceiling looked the worst. Still, everything seemed to stand firm like the fire did its best to devour the house, but the wood was too hard for it to stomach. Each went their separate ways in exploration, and Dookie found her way to the stairs, since she’d always been fascinated by houses with stairs on the inside that actually went to another floor above, practically another house. Their own house had no stairs.

She grabbed the banister but quickly let it go when she felt the soot and wiped her hand on Gid’s shirt. When she remembered it was his, she wiped a little more. The wood was in worse shape up the stairs, and she realized that must be where the fire started and why the bottom was still in decent shape. The fire had been controlled by somebody at some point, but she couldn’t imagine how. She didn’t spend much time wondering as she reached the top of the stairs and looked in the rooms as she came to the doors. The remnants of furniture still littered the floor. Two of the rooms were small with the remains of decorations revealing spaces for children. Dookie glanced in each one and made her way to the end, to the room she thought to be the master bedroom, and when she got there, she was not disappointed.

The room at the end of the hall was enormous, easily taking up half the second level. Centered against the far wall was a massive four-poster bed still intact for the most part. The canopy leaned to one side, and the drapes were more than half burned off, but it still stood. Dookie had never imagined such a bed let alone seen one. It was something out of a story book with its stacks of pillows and tasseled duvet. A chest of drawers sat against the left wall, and a high-backed chair that may have once been light green with a white floral pattern sat at a tall window, but the girl found herself walking to the bed. The mattress was nearly as high as her head.

Dookie climbed up onto the bed and looked around. She saw that one of the pillows was yellowed and sunken in the middle. The rest looked all right, though dusty and smelling of mold. She couldn’t help herself. She lay down on the bed, spread eagle and giggled. With her movement, a light flapping came from somewhere above her in the canopy, and a dove lit lightly at the foot of the bed. It frightened Dookie for a moment, then she giggled all the more.

“Oh, it’s a mess, it’s a mess, it’s a mess! Oh lordy, lordy, lordy it’s a mess! Don’t look at my house! Don’t look at my house, sweet girl! Oooo It’s such a mess, and I’m a mess! Just look at my hair! Oh lordy, Jesus, I’m a mess!”

Such a shock shot through Dookie’s body that she nearly peed in her brother’s pants. For half a second, she thought it was the bird that spoke, but when she sat bolt upright in the bed, the dove flew back to her place in the canopy. Dookie slowly looked over to see a hand on the arm of the chair at the window. It looked like a hand though it was barely more than a bag of sticks. Fear pulled her toward the opposite edge of the bed, but curiosity pushed her head around so she could see the old woman in the chair, sitting like little more than a shadow and looking out the window. Where all people were worms that consumed their way through this existence, intestines with a beginning and an end, sucking nutrients and calories from their environment and leaving waste behind while in the guise of a sentient being, the woman seemed not to consume anything at all, even the dusty air that swirled around her head stood stagnant. There was no threat here. There was barely a form, like a shell or a husk that remained from a sloughing creature. Not unlike the house in which she sat.

“Um, hello,” the girl said, scooting all the way up against the headboard so she could see the woman. Emaciated beyond what should be possible, she had thin hair that was little more than a spider’s web Dookie could see through. Her skin looked like that of a hog cooked over a pit, leathery and unmoving. Long white hairs stuck out from her chin and upper lip. She was a silhouette in front of the window.

“Hey, baby girl,” she said in her hollow voice, like her vocal cords were as dusty as the pillows on the bed. “Hey, darlin. Hey, sweet thing. What’s your name?”

“Dookie, mam.”

“Oooh, hm hm hm,” the old lady chuckled, and slowly turned her head to look at the child. “That ain’t your name, baby doll. What’s your real name?”

“Loretta,” she replied. “But everybody calls me Dookie.”

“Oh no they don’t. You’re tellin stories, hm hm hm,” the old woman looked at her from near empty sockets. It was hard to see her face with the light behind her. “I bet your granny don’t call you that. Oh, don’t look at my house, baby. Mm mm, don’t look at me. Oh I’m a mess.”

“Your house ain’t a mess. It’s burnt down.”

“Ooooooh, you’re so sillyyyyy, silly, silly, silly. You’re just a silly little thing.”

“Well, what’s your name?” Dookie asked.

“You wouldn’t believe me if I told you.”

“What kind of name is that?”

“Ooooh, he he he little miss smart ass too,” she managed to shoot her a mean look from a face that wouldn’t move. “My name’s Loretta too. How bout that?”

“Is it really!” Dookie said excitedly.

“It sure is, baby. It sure is. How old are you, sweet thing?”

“I’m eight years old, goin on nine.”

“Goin on nine,” the old lady managed to say it just like her.

“How old are you?” Dookie asked.

“You’re not supposed to ask a lady her age.”

“But you just asked me mine!” Dookie protested.

“Fair enough,” said the old lady who was also Loretta. “I’ve lapped the sun eight-seven times.”

“Good grief, that’s old,” Dookie nodded. “I don’t know if I’d want to get that old.”

“You don’t have to worry about that,” Loretta said. “What do you think is the age where you get old?”

“I don’t know,” Dookie pursed her lips and thought about it. “Mama’s thirty-eight, and she looks old. I reckon maybe thirty-five is old.”

“Well, you don’t have to worry about it, then,” cackled the old woman.

“What you mean by that?”

“You won’t live to be old,” she said flatly, any hint of a smile gone from her coriaceous face. Dookie straightened up at the statement, and she found herself sliding off the bed, though it was on the same side as the woman. Dookie never was one to be scared when she was supposed to, though it could be said she was always scared and knew not how else to be, so the flight response was lost, giving a creature an insurmountable disadvantage for survival.

“What you mean by that?” she asked the old crone.

“Oh nothing, baby, nothing,” Loretta’s tone smiled at the child, but nothing else did. “Don’t you worry one bit about it.”

“If you don’t want me to worry about, I spect you shouldn’t say it. What do you think?” Dookie had her hands on her hips and looked at the old woman like she looked at her brothers, mean as a cow ant. The old woman looked like she sat at an empty bingo card with oatmeal on her chin.

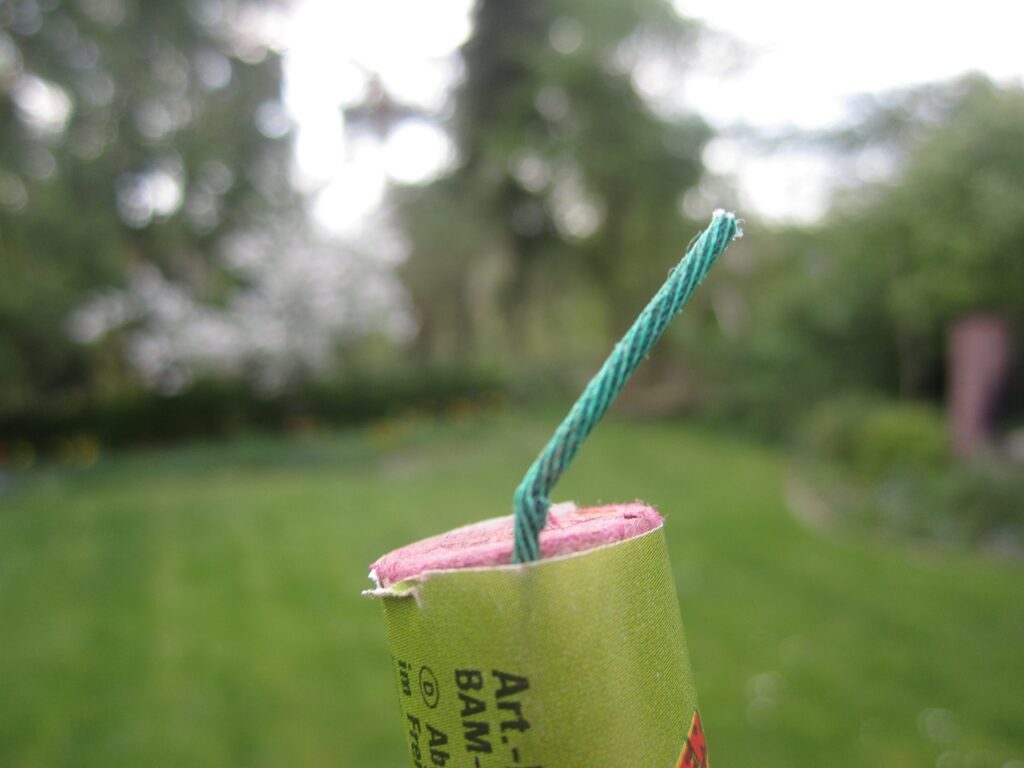

“Wooooo, he he,” the old woman cackled, “but you are a little firecracker, ain’t ya? Yes indeed, a cheap little firecracker with bulges of ruffles under your little white trash brother’s shirt. You know what firecrackers do, don’t you, little bit? They burn up real quick and go out with a bang!” she smacked the arm of chair with her bag-oh-sticks hand and a little explosion of dust flew up around it. “Tssssss, bang! Like a black cat with the paper fuse, barely enough time to get your hand away! Tee hee! Here and gone, nothing but the smell of gunpowder on the breeze, and that too gone just as fast!”

“I spect I’d rather be a firecracker than the yellow suds left on the creek bed when the water dried up.”

“Oooooo weeeeee quick, quick, quick little shit, ain’t ya? I love it!” she cackled again, and this time her torso managed to move up and down. “Firecracker, firecracker, boom boom boom! Firecracker, firecracker boom boom you ain’t worth a shift to the left, a shift to the right, a shift to the middle and fight fight fight!” She leaned forward, and Dookie felt her breath go up her nose. It smelled like wet. It smelled like mold. It smelled like the house. That same wave of needles went through her body from the top of her scalp down to her toes, and her bladder loosed again just a little bit, but she managed to pinch it back. Her lips shook, and the pain that comes to the back of the eyes just before crying hit her, but she closed it off just like her bladder.

The old woman smiled a toothless smile, her bumpy gum like a serrated blade, and she nodded slowly, never taking her sockets from the girl, but Dookie held her ground, and though she felt the water welling up in her eyes, she wouldn’t blink, she wouldn’t let it roll down her cheeks. She looked around the old woman’s face at her gums, at the long hairs coming from her chin, at her near empty eye sockets.

“You ain’t nothin but a ugly old hag,” Dookie said with a quivering voice, and the old woman turned her face back to the window, looking out at nothing like she had been before.

“But I’m old,” the old woman whispered.

“That don’t seem like nothing to brag about,” Dookie hissed back. She clinched her eyes shut and let the tears roll down. The old woman was still.

“You alright, Dook?” Aaron’s voice came from the doorway, and she turned to him, quickly pulling her shirt up to wipe her face. “Who you talking to?”

“Just this old—” she turned and looked at the chair, but it was empty. The girl stood there for several minutes staring at the yellow spot on the fabric where the head should be. “This uh—” she said softly and looked around the room until her eyes fell back on her brother.

“Nothin, Airrn, nothin. I was just playin pretend up here like I was a princess,” she walked past him, making her way down the stairs. “Let’s go, y’all!” she spoke like the leader of the band, and flapping wings stirred the dust in the house as her voice disturbed the silence. “Time’s a wastin, and I want to get to the road while I’m young.

As an undergrad, Bryant worked as a correctional officer for four years. He transitioned directly into education where he taught high school English Language Arts for fifteen years. He has been a media specialist for the past seven, and he blends his experiences and childhood into his fiction.

As an undergrad, Bryant worked as a correctional officer for four years. He transitioned directly into education where he taught high school English Language Arts for fifteen years. He has been a media specialist for the past seven, and he blends his experiences and childhood into his fiction.